There’s been some staggeringly misinformed comment

regarding Berkshire Hathaway’s partnership and equity stake with IAG (announced

on 16 June 2015).

Commonwealth Bank analyst, Ross Curran asked Mike

Wilkins (IAG’s Chief Executive) and Nick Hawkins (IAG’s CFO) one of the most naively

stupid questions I’ve ever heard. He asked whether IAG had given Berkshire 20

percent of its business in exchange for the 3.7 percent equity stake that

Berkshire made in IAG!

Let’s get a few things straight.

Firstly, the equity stake that Berkshire took in IAG is

completely incidental to the much more important partnership arrangement that

the two companies have entered into (they just happen to have been announced at

the same time which somehow managed to confuse both analysts and media alike).

They could have entered into the latter agreement without Berkshire taking any

equity interest in IAG, it doesn’t matter because that has nothing to do with

their arrangement. It just so happens that Buffett believes that IAG is a

well-run, cheap company with a strong franchise that he was happy to pay $5.57

per share for (and don’t think for one minute that he would buy a stake in any

company that he didn’t believe in, no matter what the size of that stake was).

For someone like Ross Curran to confuse this side

equity deal with the fee-based partnership arrangement suggests to me that Ross

isn’t the brightest analyst we’ve ever seen. Hey Ross, a couple of billionaires called earlier,

they want to buy 3.7% of the Commonwealth Bank and get your Board to give them

20 percent of your profits for the next 10 years– sound like a good deal for

the bank Ross? No? Then how stupid do you think IAG are?

For some media outlets like the Australian Financial Review (James Thomson) to pick it up as if it

was some great insight is laughable. On the other hand, one of the few analysts

who does seem to have had a much sounder understanding of the implications of

the deal was Jan van der Schalk at CLSA.

The really important deal was the ceding of 20 percent

of IAG’s insurance premium to Berkshire in return for Berkshire paying 20

percent of the claims and also insurance operating costs plus what Buffett

described as a large annual payment. In Buffett’s own words describing the

payment: “substantial – a payment of

a size that virtually no other insurance company in the world would pay, and

that we have never paid before.”

Buffett is a person of great integrity, so I would

accept his statement. However, because we do not know what the size of that

payment will be, we simply don’t know who got the better deal and whether it is

earnings dilutive etc. This is actually something that should have been

mandatory for both parties to disclose.

The main points are as follows:

·

The equity deal that Berkshire did was

completely incidental to the partnership agreement with IAG, anyone confusing

the two is displaying their ignorance;

·

Notwithstanding the above point, the equity

deal is a huge endorsement of IAG’s management and business model (make no

mistake, Buffett wouldn’t touch 99 percent of ASX listed entities with a barge

pole and nor should you);

·

IAG is not entering into this deal with

Berkshire under distressed conditions (unlike for example Goldman Sachs did

during the GFC), so there is no requirement to give Berkshire a great deal;

·

We do not know the details of the payments

that Berkshire will make to IAG over the life of the agreement, so any earnings

dilution calculations etc. undertaken by pseudo analysts are purely guesswork;

· Buffett has basically put a floor under the

IAG share price at $5.57, if it does go lower, you can buy at less than

Berkshire (and personally, I’m happy to);

· The benefits for IAG are the freeing up of

significant capital and greater earnings stability (IAG has made underwriting

losses in two of the past five years); and

·

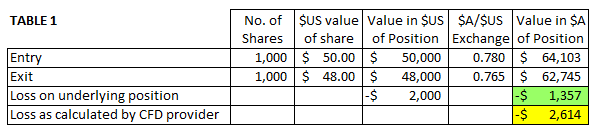

Contrary to what some pundits have written,

unless Berkshire never intends on repatriating its Australian dollar

investments, it is going to be subject to currency risk.